karakol

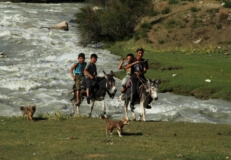

karakol jeti-oguz

jeti-oguz chong-kyzyl-suu valley

chong-kyzyl-suu valley chong-kyzyl-suu valley

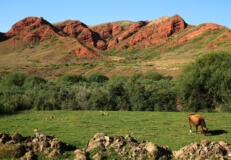

chong-kyzyl-suu valley naryn

naryn koshoy korgon

koshoy korgon tash rabat pass

tash rabat pass chatyr-kul lake area

chatyr-kul lake area chatyr-kul lake area

chatyr-kul lake area at-bashy

at-bashy bishkek

bishkek bishkek

bishkek

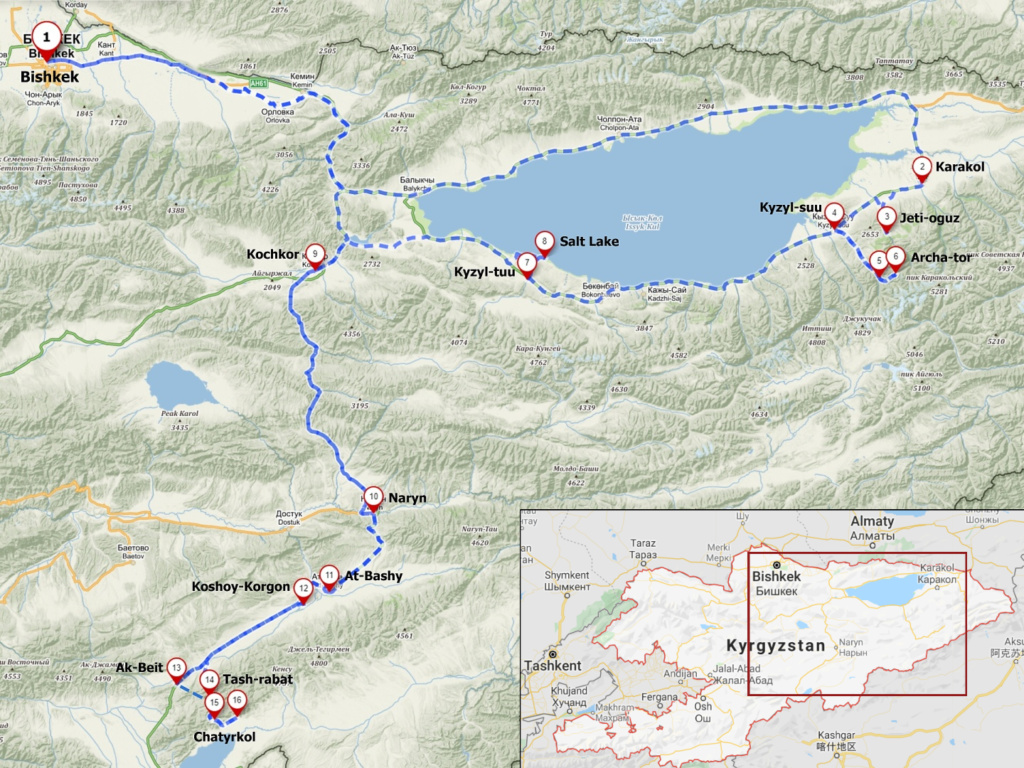

KYRGYZSTAN

2018

or

A country of mountains

and

children

Kyrgyzstan is a country of the old world and traditional values. A country where life is divided – as it once used to be in our lands – between family and work; there is usually no time left for anything else. A country where the man is an undeniable authority and the head of the family, and the woman does the cooking and cleaning and takes care of the household and children. A country where a slap upside the head can occur any time of day, but the family sticks together all the same. A country where the police can still clock your speed without the need for advance notice. It is a poor country and, for the very same reason, also full of children; it is poor economically, as well as poor on sights and other achievements of modern civilization – even the most remote Czech village can offer way more than a number of local cities which, with the exception of the impressive capital of Bishkek, look like have been hit by an earthquake or invaded by tanks not such a long time ago. The people here in Kyrgyzstan have a roof over their head each, they have cars to drive in, they got enough to eat, and they don’t have to worry about cold weather either; they just lack the time and opportunity to stop and think, to step out of the endless loop; not that they’d feel any special need to do something about it. And, last but not least, Kyrgyzstan is a land of mountains and of beautiful nature virtually untouched by humans. A visit to Kyrgyzstan offers the possibility to see – or remind oneself of – how little people really need and experience it right away.

* $1 = 70 KGS

* visa: no

* socket type: same as ours

* according to locals and other tourists, the water in Kyrgyzstan is safe to drink, we preferred to filter it first

Content

First contact, Wednesday, August 15, 2018

In Kyrgyzstan there are mountains everywhere you look, they say. And instead, beneath us lies a perfect flatland extending as far and wide as the eye can see. The sky is entirely cloudless, the monolithic blue surface has no single flaw. Yet somewhere on the distant horizon an unusual phenomenon right above ground level occurs, and at first it only seems to resemble to oddly shaped white clouds. Then, after a while the brain starts to register that these are not clouds at all, but snow-covered peaks of extremely high mountains whose sides seem to blend in with the background. This is what our landing at the airport in Bishkek-Manas (Манас) looks like.

The elegantly dressed young woman at the airport exchange office desk has apparently not completed her training yet – that’s probably not the only thing she hasn’t completed yet –, and she incorrectly takes our dollars for euros and offers us the best dollar exchange rate in the country! Pity that due to my needless worries over an unfavorable rate I’ve decided to exchange as little as possible; the general euro to Kyrgyzstani som exchange rate at the time of our trip was €1 = 78 or 79 som, while at the airport it was 76 som. So, no disaster.

Our joy over the easily acquired extra money does not last long. The plan is to go on straight to Karakol, a city located in the eastern part of the country at the foothills of the Tian Shan mountain range, and despite my initial intention not to get hooked by one of the taxi drivers, we soon end up in a taxi and throw away 500 som for a trip from the airport to the center of Bishkek. Our taxi driver is very experienced in dealing with tourists and, before we know it, he willingly finds for us a private transfer to Karakol in a luxurious, although apparently second-hand Mercedes sedan belonging to a nice young couple and their baby. In local conditions, the almost 400-kilometer-long journey with a single stop for refreshments takes more than 6 hours and costs us the rest of our money from the airport exchange office, i.e. 2500 som.

The traffic works in a squeeze in if you can style – some may even go further with the squeeze in even if you can’t approach –, and driving through corners in the opposite direction or overtaking from the right is not uncommon nor rare; the circulation runs quite orderly and safely nevertheless. Here’s why: On the main roads, there are “donuts” hiding behind every tree, setting up ingenious speed traps and collecting fines like crazy – for example, one particularly sophisticated trap was instructing drivers to decelerate to 70, after a while to 60, then to 50, then immediately to 40 and finally to 30 kph on a straight section of a four-lane road. Right at the 30 kph road sign stood a cop clocking everyone’s speed with a laser gun, but just after passing the sign all cars would accelerate back to the common 90 kph.

We could only see used cars, almost exclusively of German and Japanese make, drive around here and, as is common in these parts, we could also spot some Zhigulis, horse-drawn wagons and cows marching in the middle of the road.

The land along the road is arid and inhospitable, only in the river valleys and on the shores of Issyk-Kul Lake an insignificant vegetation is struggling for its place in the sun. The gray, neglected, and worn-out civilization is trying to do the same. The distant mountain peaks and azure blue lake stand in stark contrast to the altogether dull surroundings and immediately attract attention.

After arriving to Karakol (Каракол), we first go get a hearty meal for dinner and then slowly walk towards our hotel, or rather, guesthouse. The city center can get some credit for holding together – although, finding a bank on the ground floor of an ordinary apartment building was definitely surprising –, but only a short distance away we find ourselves in a Milovice town-like zone shortly after the expulsion of the Red Army troops from Czechoslovakia back in the 90s. We stay on the very edge of town in Janat Family Guesthouse (2 nights = 2 x 1250 som), where children play happy and carefree in the dust of an unpaved road. Just like in my younger days...

Karakol & Jeti-Oguz, Thursday, August 16, 2018

The fourth largest city in Kyrgyzstan in terms of population was, in certain historical periods, called Przhevalsk (Пржевальск); surprisingly, not because the well-known explorer and geographer, Nikolay Przhevalsky, was born here, but on the contrary – because not long before one of his expeditions to Central Asia he died here. We haven’t found any of his traces directly in Karakol, but he is buried in the vicinity and several places and locations in the area, including one of the nearby mountains, bear his name.

It is difficult to come across remarkable places in the city after all, but here’s a brief overview of the most interesting sights from our today’s city tour (in order of occurrence):

- The Grand Bazaar (Большой базар) is not significantly different from an ordinary marketplace, such as the one in Holešovice district of Prague, maybe just that the range of selection of meat, fruits, vegetables, spices and other groceries outnumbers the supply of clothing, footwear, (non)brand and further consumer goods;

- The neighboring Pushkin Park (парк им. Пушкина) is overgrown with tall grass and may draw one’s attention thanks, for example, to memorials reminiscent of old times with red star in the forefront;

- The Russian Orthodox Cathedral of the Holy Trinity (православный собор Святой Троицы) is practically the symbol of the city and one of the few buildings worth admiring in spite of its slightly dismal condition;

- After that we are approaching the main square (Центральный сквер), which has the form of a large, well-trimmed and modern park;

- We were also attracted by the new mosque (Новая мечеть), which lies slightly off the city center, but, as non-Muslims, we were unfortunately allowed to admire it from the outside only.

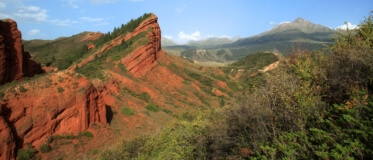

In the afternoon we made a quick round trip to the red sandstone rocks and clinic aka sanatorium of the same name at Jeti-Oguz (Жети-өгүз). We intended to finally save some money and grab a “marshrutka” for the 30 km or so ride to the attractive tourist place but could find no connection this time. Our long march and numerous inquiries to the locals on the whereabouts of a bus station (i.e. marshrutka station), only meant being sent from one place to another, then back again, and once again to the place where we’ve already been before. In the end, there was nothing else left for us than to take a taxi and give out another 1000 som.

The main formation, in verbatim translation the “Seven Bulls”, after which everything around here is called, was already partially hidden in the shade at the given time of day. That’s why the place for me, that moment primarily in the role of a photographer, was a little disappointing. However, we met two “inmates” from the sanatorium in a friendly mood, who wanted to chat a bit and take pictures together. Thanks to them I immediately started to regard our trip to the red rocks in a more positive view.

Chong-Kyzyl-Suu Valley & Archa-Tor Pass, Friday through Monday, August 17-20, 2018

We are planning to spend the next four days trekking in the Tian Shan Mountains southwest of Karakol. First, we will set out through the valley of the Chong-Kyzyl-Suu river (Чоң-Кызыл-суу) – the name means the Great Red River, supposedly from how the clay turns its lower course waters red during floods – from a small spa at an altitude of about 2300 meters to a little less than 5 km distant mountain weather station, lying just 200 meters higher up, i.e. at a moderate altitude of about 2500 mts. From there we will gradually start our ascent to the Archa-Tor Pass (Арча-төр) at an altitude of 3890 m, the highest point of our hike. If we manage to cross the pass, we mean to slowly descend back to our initial altitude in the Jeti-Oguz valley on the other side of the pass; the well-known sanatorium of the same name lies at the valley’s end. The expected route is around 35 km. However, it will all turn out differently in the end. Because...

“We are no mountaineers!” (Katka)

--- day 1 ---

there are bears in the mountains!

The night is rainy and stormy. The forecast for the next 2 days is also not very favorable; the optimist in me says it’s at least worth a try – for Karakol it keeps reporting storms, for the Kyzyl-Suu area “mere” rain and around Alakol Lake (our alternative destination) it should be sunny. Well… we can always turn back if the skies aren’t in our favor.

The marshrutka (100 som pp.) to Kyzyl-Suu town (the drivers often use its old name Покровка when calling it out loud) leaves from the same place where we tried to find a bus to Jeti-Oguz unsuccessfully yesterday and which is called the South Bus Station on most tourist maps. If we don’t want to pay extra for a private trip – no, we don’t! – we have to wait about half an hour with the others until the car is full. From Kyzyl-Suu, which lies on the main road along Issyk-Kul Lake, it is still some 20 kilometers more to the mountains. It is easy to find a taxi (800 som) that will take us there, but the ride through the mostly dull countryside, surrounded by fallow fields on one side and bare hills on the other, takes about an hour more.

At half past eleven we can finally set out!

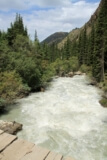

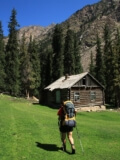

Initially, the valley is pent-up between steep rock walls, which form a natural gate here; our necks hurt from gazing up constantly. The grip of these walls is gradually giving in, and when we look at the high and graceful spruce trees relentlessly climbing up the rocks towards the sky, we feel we may even be in one of the world-famous national parks in the US instead. We continue walking through the picturesque valley along the road only negotiable by 4WDs, passing several makeshift shelters, but apart from the cows and horses, we can’t see a living soul for a long time. At the weather station, finally, there are two little boys from the yurt on the other side of the river waving and running toward us to offer us a transport across the water in their cable car. We don’t do any bargaining as would otherwise be common here and just pay them the desired 500 som.

We also accept the invitation to their family’s yurt heated to a pleasant temperature by a fire from a small stove and, once inside, meet almost the whole family – one of the five children is already grown up and therefore missing – and a young Austrian couple who follow the same path like us. Meanwhile, a light rain starts to fall outside. We get a modest meal consisting of flatbread, cream butter and a bowl of pasta, and a “free-refill” cup of black tea to drink – as soon as we finish one cup, the landlady (yurtlady?) immediately refills it. Our hosts speak Russian even worse than we do, yet we still manage to have a decent chat and not just an exchange of the usual civilities. Finally, they confirm what we already suspect anyway – there are bears in these mountains. Only a few though...

Before we say goodbye, one of the little “dealers” who has already charged us for the cable car hands me a small card with a number on it. After the relaxing visit, I am a little surprised, as there was no talk about money, but even this time I do not hesitate to pay him another 200 som.

The trail now leads to the forest, rising slowly at first and for the next hour or so our pace is cheerful. Once the trees start to recede, i.e. at an altitude of about 2800 meters, the path begins to rise sharply. On top of that, we are unaware to have missed the main turn to the pass, and consequently can hardly make it back up from the steep bed of a small stream, where we had wandered off. Fortunately, up above we can still occasionally spot the Austrian couple, who left the yurt shortly before us, and after an exhausting assault up the hill covered with dense dwarf pines, we manage to return to the trail. The weather is changing several times now; it starts to drizzle, soon after the sun shows up and opens some amazing views for us, but we conclude the final part of our three-hour ascent from the yurt as well as pitching up our tent in sight of the defiant-looking pass in the rain again. The ubiquitous cows seem undisturbed by all this and they calmly continue grazing the slopes high above us. We’ve reached the altitude of 3500 meters.

--- day 2 ---

lost in the fog

The night is uneventful. It was not too cold, nor do I suffer from insomnia at these altitudes, like I used to in the beginning of my mountaineering expeditions, any longer. No bears showed up either.:) However, it kept raining at intervals most of the night, so we are biding our time throughout the morning and wait for the sun to dry our stuff and tent well enough. While waiting, we watch a large group of marmots, who used to be a favorite game in Kyrgyzstan in the earlier days, particularly because of their fur, but also for their meat. Now they are obviously doing well, although they are shyer than, for instance, in the Tatra Mountains in Slovakia. Up here in the mountains it is actually hard to say if you are in Kyrgyzstan, or somewhere else.

We set out at 11; we’ve switched roles with our Austrian friends – they haven’t even started packing yet – and we’re leading the way up to the pass today. The trail appears and disappears again, elsewhere it splits into multiple branches left by cows, so we wouldn’t manage without my favorite app from mapy.cz in combination with the phone GPS, even though the pass is hard to miss now. The climb from the foot of the pass to its top is strenuous and long, the steep slope being mostly covered with scree provides only poor support for our feet and keeps slipping down, thus we take three steps forward and two backwards right after that. The altitude also doesn’t do us any good. At the very end of our climb I am so exhausted that I can’t even think of how tired I am – after each step my body refuses to take yet another step. We finally reach the wide top of the pass (3890 m) at about half past two.

One hour later it is decided: we are turning back. We can see three different trails, i.e. three options, leading down to the other side of the pass, but none of them seems safe enough. The surface of the slope on this side is more solid and all the trails drop sharply downwards, which is why the risk of slipping while carrying a more than 10 to 15 kilo load on our backs appears too great. We just don’t feel like it. A single wrong step would suffice to make one plunge straight down in a shower of rolling stone fragments and debris. Nor does throwing our backpacks down separately sound like a reasonable choice. The Austrians may be able to find another alternative, but we’re not willing to stay up here in the changing weather conditions any longer. In the end, we pass our fellow travelers during a quick descent – the scree has completely different qualities in the downward direction and, when compared to the climb, we’re literally sprinting now – and say our goodbyes at hearing distance.

Some 15 minutes later we are standing back at the foot of the pass again and move on without any further delay. We still look back from time to time to check if the Austrians made it to the top and whether or not they dare to climb down the other side of the pass or decide to turn back. However, their fate remains a mystery to us since a cloud layer suddenly appears over the pass and starts heading our way. The sun is still shining above us, but soon after there’s a shower, and then everything around gets covered by fog and the pass is lost from our view. We never see them again.

On the way down I’m trying to find the spot where we camped last night, but the distinct boulders now look all the same in the fog. The trail acts unpredictably just like this morning; it splits into several branches, then joins together again and splits once more, and so on. We can’t even trust the GPS now as it leads us into a dead end overgrown with wildflowers. We don’t lose hope – though we lose our nerves at times – and follow the noise of the small stream known to us from the first day burbling somewhere to our left deep down below. We try hard to maintain a downward course, even though some of the cow trails keep turning back up in the direction of contour lines. Our wandering around in the fog lasts for an hour, maybe a little longer.

Finally, we’re back on the main trail again! Though it starts to rain, the fog dissipates at the same time and we can now discern the plain at the confluence of the aforementioned stream and the mountain river Kara-Batak (Кара-батак), left-hand tributary of the Chong-Kyzyl-Suu river, emerging out from it deep below us. We can also see the first trees of the forest vegetation. It is just about six-thirty when we arrive at the foot of a massive conifer tree below the slope and call it a day.

--- day 3 ---

we have visitors!

The morning at the river is considerably cooler than up in the mountains. The rain had stopped falling soon after nightfall yesterday, but we need the sun to dry the surrounding grass, drive the moisture out of our clothes and shoes and warm our bones. Today will be a beautiful day – the rock cliffs on the opposite side of the river are already burning! The neighboring group of seven does not stay idle, they pack their stuff early and, under the weight of their large backpacks slung over their shoulders, they leave at a slow pace somewhere off the beaten track. None of them gave any indication that they were interested in our presence. Based on their behavior and the above-mentioned “clues”, I reckon they must be pros. Unlike them we stay put till 1:00 pm and cautiously meet and greet the local cows, who are also curious about us and do not hesitate to explore our campsite from up close.

In the afternoon we set out heading back to the weather station via shepherd trails. The paths lead us casually back and forth, but as we are not in a hurry, we just have to make sure to follow the river. After about an hour, there’s a light rain, otherwise the sun is shining in the sky. After another half hour we finish our delightful stroll on a small flat area in the wood just above the yurt, where we stopped on the first day. We won’t go any further today.

In the evening around five o’clock it starts to rain more heavily, but fortunately, unlike in the previous days, our tent is already up. Nevertheless, just like in the afternoon, it does not take long to clear up again. We spend the rest of the evening in our tent and go to bed at around 8:00 pm.

--- day 4 ---

the gaz is our savior

We leave the camp at 11. Like yesterday we are in no rush, so we stick for a while with the boys from the yurt, to whom, to their obvious disappointment, I only pay 300 som; this time it is for transporting us across the river and taking a picture of us. We even exchange a few words with the lady from the big house at the weather station (it’s a pity that the station does not show the forecast right away, which may have been useful a few days ago). We continue slowly on enjoying the surroundings. Thanks to the nice weather, we can now experience the places we already know in a new light.

At one in the afternoon we arrive to the small spa, where we started our hike three days ago, and enjoy a hot bath in a pool perhaps from the Stalinist era for a few “crowns” (200 som). There’s of course no one to pick us up here, so after a long rest we go on walking. It’s about quarter to three now.

From this side, the landscape along the road does not look as uninteresting as I originally thought. And we also get to enjoy it entirely as nobody won’t stop while we try to hitch a ride – as per my expectations, the traffic here is quite busy, but most cars are fully occupied or packed to the brim, or both. After about an hour to an hour and a half of walking, the forest starts thinning out and the landscape somewhat loses on its attractiveness. We have to keep going. After another hour, the walking becomes almost monotonous. Katka keeps grumbling over why nobody wants to stop for us. I reassure her by saying that “it’s the way how it probably should be” and remind her of a similar situation from our trip to the mountains in Ukraine, where we also had to wait for an “Ifa” to arrive (I, of course, mean the Gaz, which drove us from Hoverla).

And indeed! My prediction comes true: before I can take another photo of the red rocks on the other side of the river, which are, by the way, more extensive and diverse than at Jeti-Oguz, we see dust swirling in the distance beneath the wheels of an iron monster. In next to no time, our Kyrgyz “Ifa” (Right, it’s a Gaz again!) brakes in front of us. The driver’s round smiling face invites us aboard, where his entire family, i.e. his wife, mother-in-law or aunt and, statistically, three to five children, are already sitting. Plus, one other passenger. The town of Kyzyl-Suu is still a decent stretch of road away; we walked maybe half of the total of 20 kilometers.

To Katka’s certain resentment, I insist to pay a small visit to our savior for a shot of vodka, which in these parts is almost cheaper than tap water. For me, it’s the opposite, an opportunity to give a sneak peek into the lives of locals – in their home they only have a carpet and a table without chairs! There are also a few battered toys lying on the ground with which the children immediately start to play. The lady of the house hastily searches for some glasses. The dog tied to a chain at the gate obviously suffers in agony: it automatically curls into a ball in anticipation of a blow or a kick and makes one think of the most humiliated member in a monkey troop.:(

And now, let’s hop on a “marshrut” back to Karakol (150 som) and go grab some food! On the very first day, we discovered the tourist-oriented restaurant Zarina (dinner = 1200 som) right in the city center – for the sake of simplicity, I nicknamed it “Eržika“ which sounds similar and is closer to the Czech heart. Surprisingly, we didn’t need search the internet (we have got none here anyway) or consult a guidebook (we don’t have one either) to find it; to this day I am simply amazed by what instinct actually brought us here. We can recommend this place and their draft beer, Жатецкий гусь – not from Žatec despite its name – in any case!

The Feast of the Sacrifice, Tuesday, August 21, 2018

In the morning, it’s raining and cold at first, then the sun shows up. Above the mountains there still hangs a curtain of lead-colored clouds; looks like another day of typical “British” weather.:) The checkout time from the Janat Family Guesthouse is the usual 10:00 am, but today is the Feast of the Sacrifice, also called Kurban Ait (Курбан Айт), a popular Muslim family holiday, and so the landlady invites us to a festive meal before our departure, as is customary on this day. The table is loaded with food as at a banquet and, just like in the yurt, everything is drunk down with tea and with tea again – the house owners prefer it with milk.

holiday meal at the janat family guesthouse

Their sister-in-law is sitting here with us too, steamed up by the miserable conditions and poverty in Kyrgyzstan: the monthly earnings allegedly lie somewhere around $100 (according to data on the Internet, it’s around $200); corruption is widespread here, and two presidents had to step down recently because of their own greed; people used to have more than 10 children, at present the average is about 3 to 5 children and for 7 there’s a medal of honor.:) Once again, I can’t help but recall the times in our country of long ago, when my grandfather and grandmother used to tell me about their many siblings; there’s a kind of time lag of a few generations in many things here.

We want to get to the village of Kyzyl-Tuu (Кызыл-туу), which lies on the main road to Bishkek along the southern shores of Issyk-Kul Lake. Although the village itself is not significant in any way – it is so insignificant that even Google couldn’t put it in the right spot on their map –, it is the nearest starting point for a trip to the Salt Lake of Kyrgyzstan. There is no direct connection from Karakol to Kyzyl-Tuu, and the drivers going in that direction refuse to drop us out of the official bus stops defined by the timetable, which is quite incomprehensible for me in these parts, but maybe even here the rules must apply sometimes. They try to sway and persuade us that instead of the marshrutka for 300 som we should take the taxi for one thousand now, otherwise our journey will be long and needlessly complicated – the marshrutka takes about 2 hours to the town of Bokonbajevo (Бөкөнбаев) and from there we can only go to Kyzyl-Tuu by taxi anyway. We choose the more challenging option, although we later learn that it would really work out very similarly with the price. Departure from Karakol around 1:00 pm.

Bokonbajevo 3:15 pm. As it’s a holiday, only one restaurant is open and all tourists from the marshrutka including us head for lunch there (320 som). I am happy we ain’t staying here, because I would not wish to “fight” the others over the evidently scarce accommodation (un)available here. In the end, we manage to negotiate a taxi transfer to Kyzyl-Tuu for 500 som (they’re asking a double to the Salt Lake), although according to the locals it should not cost more than a hundred for two; but we are not local to afford it.:)

Kyzyl-Tuu is your typical village at the end of the world. At the main road there is nothing but a restaurant (closed today), a small store (currently open), a few dilapidated houses and a bus stop. Behind this “Potemkin façade”, however, lies a far-stretched village interwoven with a network of perpendicular dirt roads. Katka looks doubtful about finding accommodation here, as we can’t see a single hint of anything like it during our short tour among the houses, but anything can be had at the small store with half-empty shelves, even accommodation.

The owner of the store takes us to her home and lets us stay in a stand-alone guest unit (2 nights = 500 som), where, for the second time now, we encounter the complete absence of furniture or other room equipment, only a carpet lies on the floor; I suspect that this “minimalism” is rather a choice of faith or habit coming from the nomadic life in yurts than a necessity. She spreads some blankets on the floor of our bare room for a more comfortable sleep. Water is only available outside and, instead of a toilet, there’s a latrine standing at the back of the garden. On the one hand, they have hens running in the backyard, a couple sheep chewing grass in the pen and there’s no TV or Wi-Fi here, on the other hand, a decent Mitsubishi Montero and a wheel-less Volga on blocks are standing behind the house. In general, this place does not differ much from a typical Czech village house in the countryside – in rural areas the contrast in living conditions is not so striking.

Karaköl Salt Lake & Issyk-Kul Lake, Wednesday, August 22, 2018

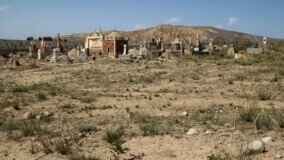

To the lake, or to be more precise, to the lakes, we go in the afternoon. After lunch – 450 som – and an unexpected meeting with two Czech bikers in the (today open) restaurant, we first set out to explore the local cemetery, which – like everything around here – looks pretty neglected, but it has a certain appeal to it at the same time. After that we easily hitch a ride to the Salt Lake, which does not have any special name on most maps and, given its repute among locals, may not even need it; the ticket (see below) states its name as Karaköl.

In the difficult terrain the cars may go no faster than walking speed, only owners of a Lada Niva can afford to step on the gas; I wouldn’t want to hike the 12 kilometers in direct sunlight. Along the way there are a few places with accommodation and restaurants, we also see several farms, and at the very end of the road is a large and well-equipped yurt town. Right behind it stands a guard booth, where we must pay a symbolic entrance fee (100 som pp.), although it could be easily bypassed in the surrounding hills. The lake does not stand out and rather resembles an ordinary Czech pond – until entering the water that is. I then experience a pleasant shock as I start to float on the water surface and feel like a straw slowly pushed out of a carbonated drink or like angels frolicking in fluffy clouds. Looking around at the kids with swim rings around their waists, one must make an imaginary cuckoo sign. There’s plenty of visitors here and many of them also spread the healing mud found here all over their bodies scaring fellow (non)swimmers by pretending to be black.

On our way back, we make a detour to Issyk-Kul Lake, aka the “Kyrgyz Sea”, which really looks like a sea. The sound of waves breaking on the shore makes me recall the final scene in the original Planet of the Apes (1968). Based on the smooth pebbles lying tens of meters away from the shoreline, one would say the water level used to reach much farther, and therefore the fate of the Aral Sea would also await this lake. But the opposite is true – in historical times the water level was significantly lower. This has been proven by underwater archaeological research, which revealed the remains of several submerged settlements below the surface.

During our walk it starts to thunder in the mountains to the south and the clouds move slowly towards us. However, Issyk-Kul Lake seems to retain its own climate and the weather remains sunny throughout our visit. We return to the dirt road the cars are taking and after about half an hour, we catch a ride back to Kyzyl-Tuu. Just as the first raindrops hit the windshield we get out of the car in front of the restaurant, where we can wait out the rain and conclude the day with a small dinner (260 som).

Funny Elsa, Thursday, August 23, 2018

Also today, we are more or less successful at hitchhiking – after about half an hour of waiting we stop a shared taxi (800 som); having a sign for Kochkor (Кочкор) has proven worthwhile. The city serves as an important tourist junction, especially for trips to Song-Kol Lake (Соң-көл). Here we stay for about an hour or two to grab a lunch (760 som).

Further to the south, we pass a zone of green, eye-catching mountains; the rest of the land remains dry and inhospitable.

In Naryn (Нарын), we easily find Kubat Tour to meet the owner and two candidates wishing to join our upcoming 3-day horse trip! I arranged the trip with Kubat before our departure from the Czech Republic and we agreed that, should anybody decide to join us, part of the initial price totaling some 39500 som for the two of us would be split among all the participants – for example, the fee for the guide or accommodation are shared, whilst food and the China border permits are paid separately.

Kubat is a typical hustler who will use every opportunity to trick people out of their money. With a little exaggeration, he’s something like the Beni Gabor character from The Mummy (1999). Luckily, this time he only managed to rip himself off – he did this by coming to the four of us and asking us to pay a completely different amount of money for the same services (in fact, he added an extra profit to the price for Katka and me). So, after a short argument with a slight dose of intensification he was forced to admit defeat and, fairly confused, eventually went back to the original amount. In the end, three of us paid the ridiculous sum of 10650 som each, and the last participant, who intends to cater for herself, paid the remainder of the above-mentioned total of 39500 som. Kubat will certainly not make the same mistake ever again!

The other participants are two charming French girls whose names could not be more appropriate! First, we got introduced to the blonde Elsa, which is also the name of our female dog. It was a bit like we got together again.:) Shortly after that, the long-haired brunette revealed her name to us: Fanny. This is pronounced like the English word in “Hi, my name is funny!” Thus, together they form the “comedy” duo: Funny Elsa!

Tash Rabat Pass to Chatyr-Kul Lake on horseback, August 24-26, 2018

--- day 1 ---

where there’s nothing

We leave Naryn under cloudy skies. During the two-hour drive to our starting point, the weather is gradually getting nicer to partly cloudy. Our driver is very calm and serene, radiating prudence and kindness. On the way, he tells us about his childhood, and it seems to me that he’s still the little boy he used to be 50 years ago. He can only speak Russian, but that of course makes no difference to Katka and me; Fanny and Elsa became friends quickly, and since they don’t speak any Russian, they talk all kind of gossip in the back seat, just like only girls can.:)

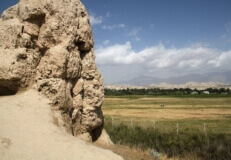

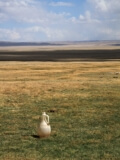

About halfway there we make a short stop in the town of At-Bashy (kg. Ат-Башы), sometimes also written out as At-Bashi (rus. Ат-Баши), for a photo of the giant horse head statue – the meaning of the town’s name in Kyrgyz. Then we make another, longer break to visit the ruins of the ancient fortress Koshoy Korgon (Кошой-Коргон) nearby. The structure today consists only of the remains of a massive clay wall and ramparts surrounding a large area of approximately square shape and the original appearance of this place can hardly be guessed. Who wants to find out if their imagination matches the reality, or simply find answers to their other questions, should visit the adjacent museum, where the reconstruction of the fortress is displayed. However, we must go on...

...to where there’s nothing. The driver points at the last village, the last outpost of civilization in Kyrgyzstan. From here to the 100-kilometer distant border with China, there is only an endless, straight road occasionally crossed by herds of sheep and goats. The road is surrounded by mountains reminiscent of the Scottish Highlands – round shapes with rocky protrusions on their tops – and a line of electricity pylons running from horizon to horizon. In an inconspicuous valley not far from an even more inconspicuous pass called Ak-Beit (Ак-Беит), we leave the road and park at a yurt that marks the beginning of our “Wild West” adventure. Although it does not seem like it at all, our current altitude is some 3200-3300 meters.

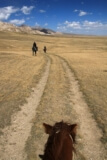

The guide has a delay. So do we – although way smaller. After some waiting, we are finally all set to go at around half past three (instead of the originally intended half past eleven). Since horse riding is a natural thing here, they do not make any fuss about it and, without further ado, the guide, with some help from the driver, have us mount the horses. The guide explains us that, unlike in Western countries, local horses are constantly kept busy and occupied, which is why they are mild in nature.

A wide valley opens in front of us, and we move forward at a slow pace, to learn how to ride and control our horses properly – to get your horse going, you have to shout “chu! chu!”; the horse should stop at a long “tuuuck!” (translation error not excluded); the rest can be managed with the bridle and reins.

As we ride through the valley, we pass more yurts that are easily recognizable by their white color – they resemble beads or pearls strung on a thread at regular intervals. After two hours we stop for a modest snack in the last yurt standing in the valley’s dead end. From here, we have to go uphill and then cross several other valleys one by one before reaching our destination for today. The sky is constantly changing now. At the same time, the sun is approaching the horizon fast and it’s getting colder. The intensity of the experience remains the same, nonetheless. All four horses tread tirelessly and willingly, carrying us on their backs. We arrive to the yurt camp at the Tash Rabat (Таш-рабат) caravanserai around half past eight in the evening, i.e. after dark.

--- day 2 ---

fata morgana

After a delicious and plentiful breakfast, we have enough time to explore the surroundings, including the aforementioned caravanserai. The massive stone building with a small dome resembles an oriental palace that would fit in the Prince of Persia game series. It used to be a roadside inn for merchants and travelers in the times of the ancient Silk Road. In other words, nothing else than a medieval counterpart of the yurt camp.

Start at 9:30 am. We are following the narrow Tash Rabat river valley to a pass of the same name – how else? – at an altitude of 3968 meters. Occasionally, the path is lined with unused farm buildings, and there are restless marmots scuttling away under our horses’ hooves. The elevation between the yurt camp and the vale below the pass is moderate, the weather is in our favor and so we overcome 400 meters in altitude in two hours of a casual ride. After a lunch-picnic break we have a similar elevation to climb to make it up to the pass. However, the horses have no problem with that, and we are up at the top in less than three quarters of an hour. Soon we can spot the Chatyr-Kul Lake (Чатыркөл) in the distance between two mountain slopes – it looks supernatural, like a fata morgana, from this far.

After a while, we descend from the mountains to the open arms of a seemingly endless plain, bounded only by steep snowy peaks far to the south and southwest – some of these already lie in China – and the mountain range behind us. We turn left to the east and continue by the road meandering through the country parallel to the shores of the giant lake, which remains out of our reach. In front of us lie the wide grassy plains and we can see perhaps even tens of kilometers into the distance. This is how I imagine the Mongolian steppe, but hard to say how close this idea may be to reality.

My search for traces of wildlife in this vast space is fruitless – there is no hint of movement on the ground, nor a flock of birds above, not even a single bird of prey soaring high in the sky. Except for marmots and some little mice – maybe lemmings – nothing else seems to live here, or it can hide perfectly. The landscape is like made of ripples, or waves, and most of the yurts at the foot of the mountain ridge and slopes to our left remain hidden till the very last moment; not only can individual animals hide here, but the same applies to entire herds of goats, as we get to see for ourselves a couple times.

Our wandering through this extraordinary mountainous landscape is long, challenging, magical. The individual yurts are separated by huge distances and we rarely manage to ask our horses to trot, which is why the guide “allows” us to have our first and only break for tea and flatbread around half past four. While here, his son joins us briefly – he’s leading another group of tourists from the caravanserai to the yurts below Shirikty Pass (Ширикты), where we will also finish our journey today; apart from this small encounter, we don’t meet another living soul on the way. We finally reach the end of today’s leg of our trip shortly before 6:00 pm.

The waiting for our very late dinner (and sleep) is long. Especially both French girls have had enough for today and they keep bragging and show their dissatisfaction rather annoyingly at times. I regret to see that they have disproportionate expectations and won’t respect local customs and manners – Fanny would like a Western-style dinner, while Elsa keeps asking for her own private room. The owners, however, remain unconcerned and continue with their own routine.

While we wait, the yurt is successively visited by more than 10 people for a chat and a cup of their favorite kumis (кымыз), a fermented drink made from mare’s milk; no idea how they all just pop out here of the blue. Many of the guests introduce themselves by name, but Kyrgyz names are so unusual that they would have to write them down for me to remember successfully. An exception that proves the rule is the house owner’s name which sounds exactly like the Czech word for (not only) the fuel that his wife adds to the stove to keep the fire burning – dry sheep dung.

Trus has (at least) two small children, a boy of about ten and a younger girl, both of whom keep us company all evening. When the dinner is finally served, the little girl overthrows a bowl of hot soup on herself by accident and the ongoing peace is gone. The kids’ mother makes the situation worse by blaming the boy for this incident and lets go of her anger by slapping him hard, which only a few Czech parents would dare nowadays. And now both kids are crying.

In the austere conditions far from civilization, everyone is totally clueless about providing first aid for burns: nothing like “nine-one-one” works here (not to mention the non-existent mobile signal); toothpaste is the closest substance to disinfection (this is also my evidence that it is not as universal as is sometimes claimed either:)); no one will go riding with the little girl on a horse (let alone driving by car) to the 100 kilometers or more distant At-Bashy at night. To ease her pain and calm the situation down is, among others, possible thanks to the First Aid app, which I have fortunately downloaded on my mobile; thumbs up to the Czech Red Cross. In any case, this night is not gonna be a short night...

--- day 3 ---

the first snow never lasts

There are scissors hanging on the wall instead of a picture. The windowsill is decorated with a car battery instead of a flower. This battery supplies power to a single dim bulb suspended from a ceiling made of branches. Who can tell me where-we-are?

I wake up on the floor of a small zemljanka, a dugout shelter, semi-recessed into a slope by the yurt, in which Fanny and Elsa spent, by their own account of events, a “romantic” night with the guide (and Trus’s family). Katka and me shared the zemljanka with a young couple, probably another of Trus’s sons, and his wife, or – to avoid unfair preference – they with us. We took the liberty of telling a little white lie to our benefactors the previous evening, because a man and a woman may not share the same bed/sleeping bag/floor here unless they are married; and we are not. Katka, next to me, is already awake and claims that the snow has fallen outside!

“I’m not falling for that one!” I already know her jokes of this kind. However, the surrounding landscape is really covered in a light coat of white and more snow keeps falling merrily from the sky. The zemljanka owners have also gotten up and they are setting up the table, which usually takes the center stage in a room, for our breakfast no. 1. It may be just an ordinary risotto, but there’s enough for everyone and plenty more. The son of our guide joins us with his group, a young Canadian couple, and a guide-coworker, so what four of us started, eight are now going to finish; the food is a joy in Kyrgyzstan and it’s only real when shared.

Since the girls from France prefer to sleep in, we join them for breakfast no. 2, which is held later in the yurt and no one is, of course, allowed to miss it. This time cooked buckwheat with a cucumber & carrot salad is served. Tea and flatbread are also ready for the taking. Meanwhile, the snow is slowly disappearing from the surrounding area, but it may still hold higher up. Our discussion about the success of “Operation Shirikty” during breakfast is therefore... well, fast.:) We are not equipped for snow and according to the guide the Shirikty Pass is a krutoj pereval at an altitude of more than 4000 meters. Due to the uncertain weather and upon his recommendation, we set back by our yesterday’s route for the caravanserai. We start at half past eleven.

Although the weather is still stable on this side of the mountains, the guide wants us to cross the Tash Rabat Pass as soon as possible and keeps urging us forward ceaselessly. As a result, we avoid the road completely this time and go directly for the point where we will be turning back up to the pass. We get here in about two hours after leaving the yurt. The pass above us is obscured by clouds and, during our further advance, greets us with light hail, which does not last long and after crossing the highest point it turns quiet again. After descending into the valley, we can take a break for lunch and complete the rest of the trip at a less hasty pace. Around five in the evening, the guide hands us over to the driver at the caravanserai campsite.

Above the mountains there hangs a curtain of gray clouds, but we are going back to the main road for At-Bashy, which has a downward direction now. Before us, under a partly cloudy sky, opens a unique view of the entire valley of the Kara-Koyun river (Кара-Коюн). It is not only thanks to this show which takes place in front of the windshield resembling a large movie screen, that the trip seems to go faster this time, and we are back in Naryn even before dusk.

Bishkek, Monday & Tuesday, August 27-28, 2018

We arrive to Bishkek (Бишкек) on Monday around half past four in the afternoon, i.e. after about a 5-hour drive by marshrutka (1000 som) including a mandatory break for a fast food (210 som) in one of the numerous diners lining the main roads of Kyrgyzstan. The driver drops us off in the eastern part of town, from where we march to the center and on to our hostel near the Osh Bazaar in the west side of town. Thus, we spend today’s afternoon and most of tomorrow sightseeing this city of a million souls.

Bishkek can stand comparison with any major city located in the opposite direction of rotation of the Earth and within Kyrgyzstan it resembles an oasis in the middle of the desert, although it is impossible not to tell which country it belongs to. As if it belonged here and not at the same time, as if it were lying on the border between the old and new world – with its wide avenues and boulevards, huge squares, beautiful, green parks, majestic monuments, modern restaurants and, last but not least, spectacular mosques, it can reach the same rank as many Western cities, while buildings and monuments from the Soviet Union era, remnants of the personality cult, gray and peeling houses, dusty sidewalks and roads, or a minimum of shopping centers sweep the scales’ hands to the other side. And that’s good. Otherwise, it wouldn’t make much sense to come here.